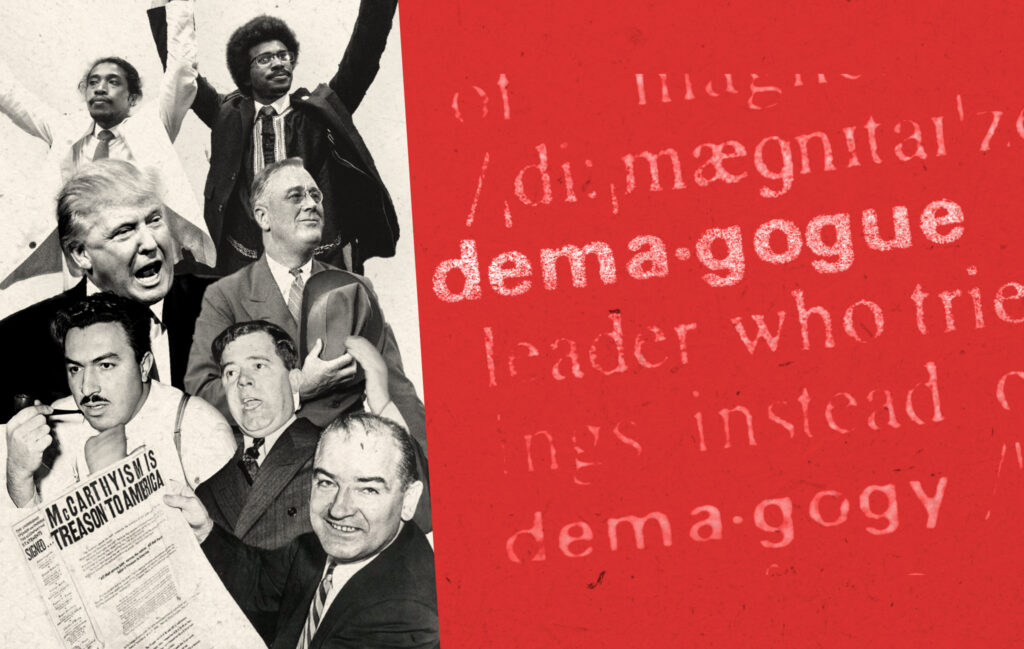

We live in an age of demagoguery. New technologies and social media give performative politicians and conspiracy theorists powerful platforms from which to rile up their followers. Donald Trump appears likely to be the GOP nominee once again, notwithstanding the insurrection he incited in his failed bid to overturn the last election. In Congress and across the country, elected leaders are rallying supporters with heated rhetoric.

In Tennessee, for example, two Democratic state representatives recently used a bullhorn on the floor of the House to lead protesters chanting demands for gun control from the gallery. The Republican Speaker likened this episode to the January 6th riot, insisting that the disruption in Nashville was “at least equivalent, maybe worse, depending on how you look at it.”

But how, exactly, should we look at it? Are these two acts of demagoguery, and the actions of the crowds they galvanized, more or less equivalent? Or can we distinguish between different instances of demagoguery and how they bear on constitutional democracy in the U.S.?

We might begin by asking, what is a demagogue? Merriam-Webster offers us a serviceable starting point:

“Demagogue:

1 : a leader who makes use of popular prejudices and false claims and promises in order to gain power

2 : a leader championing the cause of the common people in ancient times”

The dual aspects of demagoguery require us to wrestle with this concept more than we have been in the years ahead. We need to develop the capacity to distinguish pernicious demagogues from those engaging in potentially beneficial forms of democratic leadership. Two recent books underscore this imperative and equip us to make such distinctions.

Taking Donald Trump Seriously and Literally

The first book is Jennifer Mercieca’s Demagogue For President: The Rhetorical Genius of Donald Trump. Mercieca is a scholar of rhetoric and communications at Texas A&M. She grounds her discussion of Trump by noting demagoguery is a form of leadership that can be heroic or dangerous, depending on the circumstances. The former is distinguished from the latter by its accountability to the people and respect for the institutions of democracy through which that accountability is rendered. Trump, with his sustained attempts to cloud, undermine, and escape democratic accountability, does not fit the heroic mold.

That said, Mercieca takes seriously the rhetorical acumen of Donald Trump. Most of his critics and political opponents deride him as a narcissist, toddler-in-chief, boor, etc. Whatever else he might be, Trump is cunning and shrewd. Indeed, he has repeatedly demonstrated the preternatural political and rhetorical savvy needed to overcome formidable obstacles (some self-imposed) to dominate his party and win the presidency. He currently stands a one in three chance of residing at the White House again. We dismiss him at our peril.

Perhaps the most important contribution Mercieca makes in her book is her explication of why and how Trump exploits the demagogue’s rhetorical toolkit to rally his supporters and confound his opponents. The tools include, in the original Latin, argumenta ad populum (appeals to the crowd), ad hominem (attacks on the rival, not their argument), and ad baculum (threats of violence, intimidation). Trump likewise deploys the rhetoric of paralipsis (e.g., “many people are saying” rumor-mongering), reification (objectification, othering) and a simplistic American exceptionalism to serve his purposes. His crude but nonetheless masterful deployment of these tools have enabled him to rise, survive, and remerge after his frequently predicted and exaggerated political deaths.

While Trump uses age-old rhetorical techniques, he does so in novel ways that are well-suited for our discombobulated media environment. Mercieca holds that critics who see Trump simply (and simplistically) as an authoritarian, a demagogue seeking to be a modern-day Mussolini, misunderstand his methods and goals. Trump brings the well-honed approach of an attention-grabbing celebrity, business huckster, and reality TV host to his demagoguery. For him, it is all about the spectacle:

“He plays the spectacle for what it is. He is its creature, its essential qualities. If we put Trump’s demagogic rhetorical strategies into a spectacle frame, we ask different questions than if we judge him based on whether or not he is an authoritarian. As a spectacular demagogue, Trump uses strategies that he thinks will make great or compelling TV and dominate the news cycle. He asks: What will attract attention? What will divide people into teams to cheer for (or boo against) the story’s main character, Trump? What kinds of plots will distract from other stories? What will drive outrage and engagement?…[He] is the modern-day P.T. Barnum of attracting and keeping our attention and, like Barnum, Trump isn’t afraid to use humbug if it suits his strategic goals.”

Ultimately, the point of Mercieca’s rhetorical analysis is to take observers, commentators and citizens behind the curtain of Trump’s demagoguery:

“Perhaps the best way to neutralize a dangerous demagogue is also the most democratic way: to let the demagogue’s audience in on the demagogue’s strategic game so they can decide for themselves what they think about it….Recognizing that demagogues try to prevent us from thinking critically about their demagoguery, we must learn to think about rhetoric and arguments like demagogues do.”

Can Demagoguery Be Constitutional?

Charles Zug, in Demagogues in American Politics, develops a similarly powerful and incisive contribution to our collective capacity to understand and judge demagoguery. A political scientist at the University of Colorado-Colorado Springs, Zug brings the lenses of American political development, constitutionalism, and political thought to bear on this form of leadership. His book overturns conventional wisdom by contending that not only can demagoguery be compatible with liberal democracy, at times it may be necessary to realize the Constitution’s ends.

Conservative constitutionalists have traditionally held that demagoguery is by its very nature harmful and to be avoided in the United States. They read our constitutional arrangements, focused on fostering a politics of “reason-giving” and deliberation, as a system designed to prevent precisely this perverted form of democratic leadership. More recently, Donald Trump’s critics and opponents have echoed this blanket rejection of demagoguery in American politics.

In Zug’s analysis, however, demagoguery is a weapon that can be used more or less responsibly, to defend or undermine democracy, depending on the circumstances and means of its deployment. He argues that the ultimate end of the Constitution and the institutions and processes it establishes is to promote the general welfare. At certain times, arrangements meant to foster reasonable deliberation can fail and actually impinge on the general welfare. In those instances, political leaders may be justified in resorting to impassioned, even inflammatory rhetoric meant to stir public opinion, i.e., demagoguery.

To be clear, Zug is not giving politicians an open license to demagogue. He lays out when and how they might credibly defend resorting to this fraught form of democratic leadership in ways that comport with our constitutional tradition:

“Defensible demagoguery must be integrated with an explication of the purpose and justification of the demagogic rhetoric in question….The plausibility of an argument of this kind would hinge ultimately on two questions: (1) whether there is sufficient reason to think that not using demagoguery would fail to move the audience, and (2) whether such a failure would result in some genuine harm to the polity. Defensible use of demagoguery thus hinges on the tenability both of the diagnosis offered and of the orator’s explication of their own rhetorical conduct.”

Zug overlays an additional constraint–the institutional purposes of the three branches of government. These varying purposes differentiate, and do much to determine, the credibility of claims that officeholders in each branch can make in defense of any resorts to demagoguery. Based on these institutional logics, Supreme Court justices have the highest bar to clear, members of Congress the lowest bar, and presidents fall somewhere in between.

Zug brings this framework to life in several illuminating case studies of demagoguery by federal office holders. These include the prominent cases of Huey Long, Joe McCarthy, and Donald Trump, and the less discussed cases of Supreme Court justices Samuel Chase and Antonin Scalia. These leaders went to different lengths to justify their use of demagoguery, but in Zug’s analysis they all ultimately fell short of doing so.

Zug presents two case studies of defensible demagoguery: Congressman Adam Clayton Powell’s advocacy of desegregation and civil rights for African Americans and President Franklin Roosevelt’s arguments for court-packing. Zug highlights how Powell and Roosevelt, consistent with the responsibilities of their offices, argued persuasively for their departures, meeting his two-part test described above. In both cases, the protagonists effectively contended that remaining in the realm of reasoned discourse and respecting established institutional procedures would serve to undermine the broader purposes of the Constitution.

In his conclusion, Zug warns against the assumption that our constitutional order precludes the legitimacy of demagoguery, and that we should therefore condemn all instances of it. He flags a paradox: sweeping and moralistic denunciations of this form of leadership leave us at a loss when it comes to judging the growing numbers of political leaders resorting to it. “Not all cases of demagoguery are equal,” Zug observes,

“Demagogues can become constitutional in that they can be recruited to advance constitutionally enjoined ends. Demagoguery can be good or bad in the same way that democracy can be good or bad, because the same normative force that legitimates democracy also legitimates demagoguery; the two are inextricable, and our only choice is to face demagogues soberly.”

Demagoguery in the Name of Democracy

Against this backdrop, how should we think about the demagogic episode mentioned at the outset led by Tennessee state representatives Justin Jones and Justin Pearson? Let’s consider the basic facts of their case:

- Jones and Pearson, representing districts in Nashville and Memphis, respectively, insisted that the state legislature must respond to the March 27 murder of three schoolchildren and three adults in Nashville. This was the sixth mass shooting in Tennessee since 2015. But the GOP supermajority in the House blocked their efforts to force the issue of gun violence onto the legislature’s agenda.

- The Republican dominance in the House has been cemented in place through bare-knuckled redistricting. To be sure, it is a solidly red state, but the district lines skew representation in the House to an even deeper shade of red. While Donald Trump won 61% of the vote in 2020 and GOP Governor Bill Lee won 65% of it in 2022, Republicans hold 82% of the House seats. NBC News reports that “half of the Republicans in the chamber ran totally uncontested in 2022. Of the 38 who did have an opponent on the ballot, all but four won their election with 60% or more of the vote.”

- On March 30, roughly a thousand protesters organized by a local mothers’ group flooded the Tennessee State Capitol and the chamber galleries to demand action on gun violence. Reuters reports that “demonstrators held aloft placards reading ‘No More Silence’ and ‘We have to do better’ while chanting ‘Do you even care?’ and ‘No more violence!’”

- During the protest, after failing in their repeated attempts to get their Republican colleagues to consider solutions to gun violence, Representatives Jones and Pearson went to the House chamber’s well. Without being recognized to speak, and ignoring the presiding officer’s efforts to impose order, they used a bullhorn to lead protesters in chants, e.g., “No Justice, No Peace!”

- Democratic Representative Gloria Johnson of Knoxville, the state’s third largest city after Nashville and Memphis, did not use the bullhorn but nonetheless stood in solidarity alongside Jones and Pearson.

- The protest remained peaceful throughout. Politifact reports that, contrary to Fox News claims, the protesters did not come on to the House floor, there was no destruction of property, and state troopers eventually cleared out the crowd without any arrests.

- On April 6, the Tennessee House voted to expel representatives Jones and Pearson for violating House rules and decorum, and fell just short on a vote to expel Johnson. Before their expulsion, Jones and Pearson lamented the grievous harm being inflicted on the people they represent by the legislature’s refusal to deal with gun violence. This inaction, they held, left them with no choice but to break with decorum in the name of democracy.

- Shortly thereafter, the Metro Nashville Council and Shelby County Board of Commissioners, the bodies authorized under state law to fill the vacant seats, reappointed Jones and Pearson, respectively.

- On April 28, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee announced plans to call a special legislative session later this summer to consider measures to counter gun violence.

To my mind, the actions of Jones and Pearson can reasonably be classified as examples of the heroic or constitutional forms of demagoguery described by Mercieca and Zug. There is no doubt that they led as demagogues in this instance, but in ways that ultimately served the purposes of democracy. I expect we will see more of this sort of leadership in states from minority party representatives when their constituents’ values and interests are being ignored by entrenched supermajorities. Provided there is no violence or intimidation, the disruptors can credibly defend their stances, and they submit to democratic judgment, this will signify not the demise but resilience of democracy.

Indeed, by forcing forbidden issues onto the legislative agenda and sharpening conflict over them, Jones and Pearson are following an honorable path in the American political tradition. Consider that, after leaving the presidency, John Quincy Adams was elected by voters in Plymouth, Massachusetts to represent them in the House. There he led a cagey and determined effort to bypass the “gag rule” imposed by supporters of slavery that prohibited Congress from debating the thousands of anti-slavery petitions it received. Adams’ unstinting advocacy, in violation of established norms and rules of decorum, earned him the sobriquet of the “hell-hound of abolition.” John Quincy Adams narrowly escaped his congressional opponents’ attempt to censure him for his actions, but history has credited him and censured them for their roles in this fight.

To uphold democracy in America, we have to judge our politicians, and not simply on their agenda, effectiveness, and respect for norms and institutions, though those are important considerations. More fundamentally, we must judge whether their leadership respects and reinforces the values and system of constitutional democracy we use to govern ourselves. We are especially obliged to do so when the leadership is constitutionally fraught, as demagoguery always is. Blanket acceptance or condemnation of political leaders’ behavior, particularly when driven by our partisan preferences, or out of respect for institutional norms, may be comforting. But it is inadequate for the responsibilities we now face as citizens of a beleaguered republic.